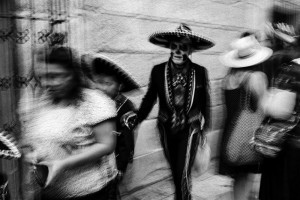

OAXACA — There is less distinction in Mexico between the great passions of love and death. The two are acknowledged in life and depicted in art as intertwined, inseparable, a reminder of the other and the fleeting nature of human pursuit, the sweetness of the sun, the chill of the grave, the ever-present skull beneath a lover’s face, and the knowledge that a flower will wither even as it has yet to bloom. Death is not kept in flabby secrecy and bureaucratic idiom, nor is love, nor the warring natures of the divine and the damned. After the corrida de toros, women sit on the corpses of bulls, displaying their beauty as the gutters run red. The air smells of hot flesh, perfume, blood, and earth. The matadors repeatedly face martyrdom by piercing and trampling while wearing tights that expose the outline of all their parts. People dress well, men and women, poor and rich, at the cantina, in church, in the street, at work.

Holidays still have meaning in them, and life has not become so compartmentalized that there is automatic hypocrisy in dichotomy. Prayer and intoxication, sex and death, sacred and secular, God and the devil, heroism and corruption, bravery and cowardice. These exist – we all know they exist — and in Mexico there is no pretense that they do not, that they are somehow not together in all of us.

Holidays still have meaning in them, and life has not become so compartmentalized that there is automatic hypocrisy in dichotomy. Prayer and intoxication, sex and death, sacred and secular, God and the devil, heroism and corruption, bravery and cowardice. These exist – we all know they exist — and in Mexico there is no pretense that they do not, that they are somehow not together in all of us.

We wring our hands over the commercialization of our secular and nationalistic holidays, but holidays have always meant opportunity for people to feast and for merchants to make money. We should wring our hands and gnash our teeth not because profit exists alongside the sacred but because we have reduced the sacred to flaccid spectacles of forgotten meaning. We blame the bogeyman of capitalism and mercantilism for our own loss of passion, our own turning away from the deeper mysteries, our own willingness to sterilize passion out of fear, the vain hope we can buy off death if we never look at it. What are Christmas and Easter but meditations and celebrations of birth, death, and rebirth: holidays that have combined Christian belief with the ancient mysteries of things that have always weighed on the minds of men because they are the great mysteries. We have cloaked their meaning in Santa Claus and presents, rabbits and candy: attenuated myths removed from understanding.

Halloween seems just a little closer. In the air, we can feel the world begin its process into winter, smell the dying of the year, and imagine the shades of the dead walking in autumnal night. We feel, in the coming cold, another year of ourselves passing into history. The ghosts and devils, heroes and harlots whose guise we assume, are more readily recognized as symbols of our hopes and fears than the insipid and degraded mythologies of our other celebrations. Still, we confine this to one, mostly gelded night, talk more of treats than of tricks, and speak little of the dead. Like our other holidays, we have lost remembrance. We do not put ourselves in the line of our ancestors and descendants, pray for their souls and remember their deeds, and we have no fear of God or the devil nor do we have absolution or joy.

dead walking in autumnal night. We feel, in the coming cold, another year of ourselves passing into history. The ghosts and devils, heroes and harlots whose guise we assume, are more readily recognized as symbols of our hopes and fears than the insipid and degraded mythologies of our other celebrations. Still, we confine this to one, mostly gelded night, talk more of treats than of tricks, and speak little of the dead. Like our other holidays, we have lost remembrance. We do not put ourselves in the line of our ancestors and descendants, pray for their souls and remember their deeds, and we have no fear of God or the devil nor do we have absolution or joy.

As during Holy Easter Week, Semana Santa, the ancient feast days are acted out in Mexico during Day of the Dead, Dia de Los Muertos, the period between October 31, November 1, and November 2, the triduum of Allhallowtide: All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day. And like our Easter and Christmas, the Christian celebrations syncretize earlier traditions and bear their echoes in ritual and symbol. Unlike Semana Santa, that celebration of the crucifixion and resurrection so marked in Latin America by solemnity, clouds of incense, and funereal music, Dia de Los Muertos is markedly wilder, the music happier, the crowds of skeletal celebrants smiling and happy. And why should this be otherwise? Easter is the recognition of the torture and execution of Jesus Christ our saviour, a ritual reminder and meditation upon the death of the living God to atone for the sins of mankind. During Dia de Los Muertos we meditate upon our own deaths, the fleeting nature of life and love and the impermanence of human beauty and mortal pursuits. Why should we not then dance and sing and drink mezcal in the hot sun and wonder at the beauty of fair ladies painted as the dead but still very much alive?

Post a Comment